Hundred Kingdoms

Forged by descendants of the refugee masses of the Old Dominion, the Hundred Kingdoms stand divided in borders, but united as a bastion of humanity’s spirit, grit and honor.

“What were once myths and legends are now pieces on the chessboard and the villains of our childhood’s tales are now players in the game. We must not lose who we are. But we must still play the game by rules we’ve never played it before.”

– King Fredrik of Brandengrad

![]() Sheltered by the selfless sacrifices of the last Legion, the refugees that managed to escape the cataclysm of the Fall would survive the Long Winter that followed and, in time, prosper to found one of the largest and most diverse bastions of human civilization on Eä. Today, the Hundred Kingdoms extend from the sheltered Heartlands by the Bitter Sea, all the way to the lands of the Russ, which stretch against the Claustrine Mountains, before one descends into the corruption and darkness spawned by the Fall beyond them.

Sheltered by the selfless sacrifices of the last Legion, the refugees that managed to escape the cataclysm of the Fall would survive the Long Winter that followed and, in time, prosper to found one of the largest and most diverse bastions of human civilization on Eä. Today, the Hundred Kingdoms extend from the sheltered Heartlands by the Bitter Sea, all the way to the lands of the Russ, which stretch against the Claustrine Mountains, before one descends into the corruption and darkness spawned by the Fall beyond them.

Despite the best efforts of the Orders, the spiritual successors to the legendary last Legion, the Hundred Kingdoms have been riven by war almost from the moment the first desperate refugees laid eyes on the Bitter Sea. Peace has only visited their lands twice: once, upon the return of the Orders from the Claustrine Wall at the onset of the Long Winter, and again during the rule of the Armatellum dynasty that managed to briefly unite the Hundred Kingdoms under one banner and found the Tellian Empire.

The tragic end of that dynasty saw the Empire plunged into chaos and brought the resurgence of the Hundred Kingdoms. Today, the Hollow Throne and a few key institutions are all that remain of the Empire while, year after year, would-be Emperors and conquerors perpetuate the cycle of violence that makes an Empire a quickly fading dream.

With Spires and Dweghom Holds scattered in their lands, pressured by the constant aggression of Nord raids and riven by centuries of internecine warfare, the Hundred Kingdoms are militarized to an unprecedented degree. The feudal system that underpinned the old society is buckling under the assault of an increasingly complex trade-based economy and an ever-increasing demand for manpower. A new class of professional soldiers has risen, men and women who fight not for land or obligation but for simple gold. While these men-at-arms are covering the demand for manpower across the Hundred Kingdoms, they also represent a significant destabilizing force. Power is starting to shift away from the traditional landowning aristocracy and into the hands of their rulers, who hold the rights of taxation and can use that coin to purchase the manpower they need to keep their recalcitrant vassals under control.

To this volatile mix, one must add the growing assertiveness of the Faith. Their extensive holdings, and alliances with the Nobility, are allowing them to circumvent the old covenants and field a military force through proxies. As long-disused muscles are being flexed, the ancient animosity between faiths is coming to the fore, with the Theist and Deist dogmas marshaling their power and supporters, getting ready to take their arguments from the religious Councils and onto the battlefield.

Standing against this rising tide are the Orders, warriors without peers whose prowess verges on the supernatural, a mantle and burden inherited from the shattered Legion that birthed them. Bound by their common cause to protect mankind from a hostile world, the Orders are split along ideological lines on how best to do this. Ranging from the fanatical devotion of the Order of the Sword to the calculated interventions of the Order of the Sealed Temple, the Orders are the strongest check to the rising power and aggression of the Church and the all-too-numerous local rulers.

Allies in these efforts can be found among the remaining institutions of the Empire. In the desperate days that followed the collapse of the Tellian Empire, the Imperial Conclave deemed the accumulated wealth of the Imperial family too great to risk distributing amongst its members. Thus, the Office of the Imperial Chamberlain was founded to manage the estate until a new Emperor could be elected. Though his direct power is limited, the Imperial Chamberlain holds tremendous influence among the Imperial institutions he funds and supports: the Mint and its Gilded Legion, the Collegia and the Imperial War Colleges, as well as the Imperial Courts, often the last hope of the common man to receive a just ruling. Despite the best, and often stubborn, efforts of the most influential of sovereigns, these institutions have retained a measure of autonomy and independence, providing a stabilizing factor among the claimants of the Hollow Throne in no small measure due to the terrifying efficacy of the Steel Legion, the only Imperial Legion that refused the call to disband following the death of the last Emperor.

As a result, the forces of the Hundred Kingdoms can display tremendous variety, from a staunchly traditional feudal levy, reinforced by men-at-arms hired by a sympathetic Church, to an eclectic mix of professional Imperial Legionnaires and feudal allies, stitched together by the Imperial Chamberlain and backed by the brutal pragmatism of the Order of the Crimson Tower.

The Powers That Be

Internal turmoil is no stranger to the Kingdoms, having forged them into the diverse military powerhouse that they are today. With roots and enmities running deep in the Kingdoms’ history, four influential groups work behind the scenes to shape their future.

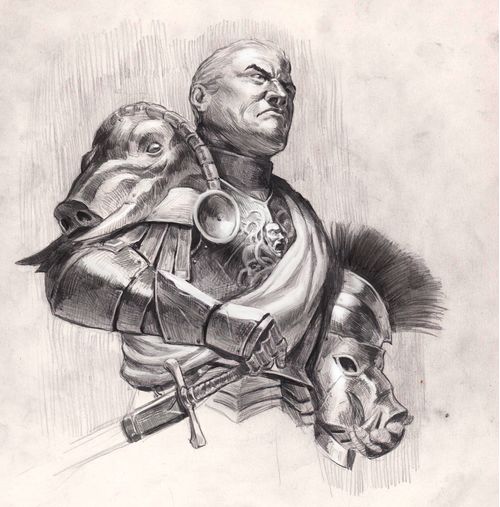

Nobility

Nobility Orders

Orders Imperial Remnants

Imperial Remnants Faith

FaithNobility

In the early days after the Fall, when each Kingdom was but a fortified settlement on the shores of the Bitter Sea, nobility was defined by the ability to enforce one’s claim to it. The arrival of the Orders simplified matters. No petty tyrant or bandit king could hope to challenge an opponent who was backed by the Orders’ Brethren. This quickly resulted in a consolidation of power amongst those noble houses that courted the support of the Orders. As the Long Winter ended and the population exploded, spreading to more distant lands, the limited manpower of the Orders saw this simple paradigm come to an end.

Freed from the shackles the Order had imposed on it, the influence of the Theist Church quickly grew, forming a symbiotic relationship with the nobility. The nobles funded and protected the Church, while the Church expounded on the Divine Rights of the nobility, filling the void left by the Orders in the ratification of nobility’s claims. Legitimacy was no longer determined by the acquiescence of the nobility to the wishes of the Orders, but a divinely granted mandate, regulated by the Theist Church. Still insufficiently manned, the Orders had to find new means of controlling nobility. After the disaster of the Red Years, they found the tool they sought in the nascent Tellian Empire.

The rise of the Tellian Empire, as well as the spread of the Deist Creed, put an end to this newfound freedom of the nobility. Nobles either bent the knee to the new Emperor or were replaced. Backed by the Orders and supported by the same Church doctrine, the Emperor seemed unassailable. But while many resented the governorship of a distant figure, few could argue that the nobility flourished under Armatellum rule and the stability it provided.

Today, with the Emperor gone and the Church and the Orders at each other’s throats, the nobility are a hereditary self-proven fact, ruling the Hundred Kingdoms almost unimpeded. They are broadly split into two groups: the Imperialists, who wish to see a new Emperor elected, and the Sovereigns, who wish to see an end to the very idea of Empire. Ironically, both of these factions see the future in the Imperial Conclave, a gathering of all of the potentates in the Hundred Kingdoms, called every four years to issue decrees with the authority of the Emperor. Putting their differences aside, both groups have come together in the Conclave to muzzle the Orders, preventing them from intervening in their internal politics, curb the power of the Chamberlain and the remaining Imperial institutions, and limit the influence of the Church.

Free from the influence of a higher authority, the nobility have turned to their personal agendas with a vengeance. The very name of the Hundred Kingdoms is a result of the influence of the nobility. Their power games in the Conclave result in an almost daily re-drawing of the political map of the Tellian Empire, as inheritance, betrayal and marriage have become favored tools, with armed conquest reserved as the last argument of Kings.

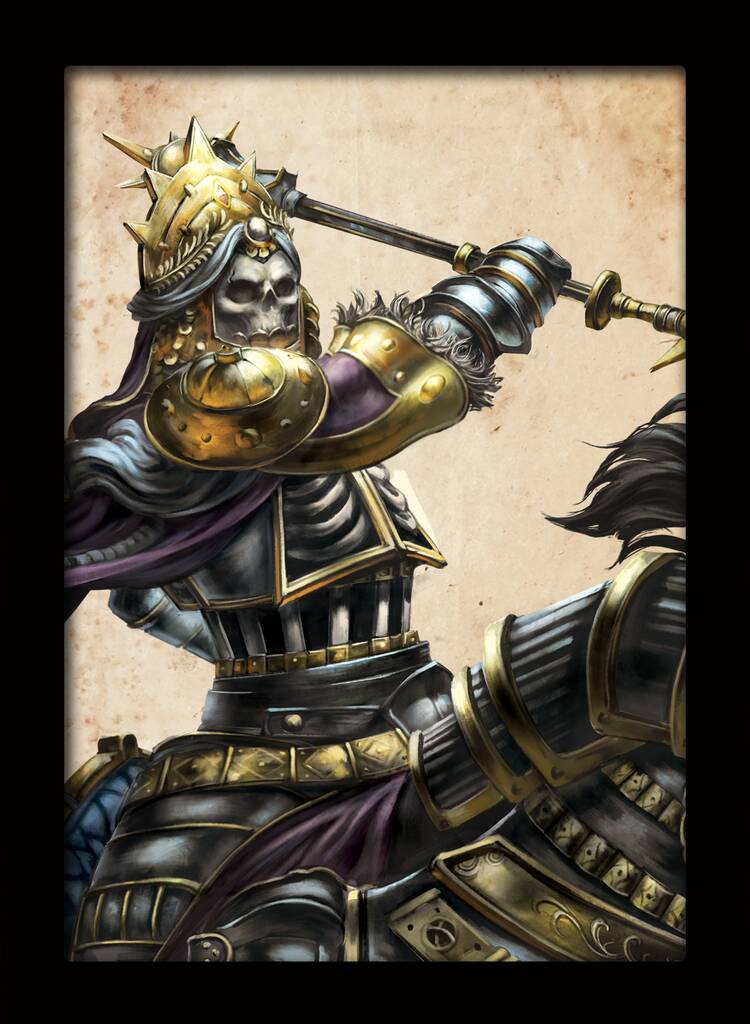

The Orders

The Orders are the oldest and most powerful armed forces in the Hundred Kingdoms, created following the collapse of the only Legion that survived the Fall of the Old Dominion. The battles and sacrifices, that the Legion undertook to shield humanity from the nightmares of the Fall, took too heavy a toll on its surviving members and fragmented the Legion. The Orders today are direct descendants of the original diaspora, each Order seeking to do its best in protecting humanity from what it sees as the greatest threat.

Sometimes, this is through direct action, following in the more martial traditions of the Order of the Sword or the Order of the Crimson Tower. More often than not, it is through the tremendous influence the Order of the Sealed Temple and its vast wealth, backed by the subtle threat of military reprisal. They were the force behind the establishment of the Militia Act that severely curbed the power of the nobility, as well as the main reason the church has not been able to convince the Imperial Conclave to rescind the laws limiting their armed forces to bodyguard details. Looking further back, one can see their support in the very foundation of the Tellian Empire, the spread of the Deist Creed and establishment of the Guild system. Whether it is with an iron gauntlet or a velvet glove, the Orders’ hand can be seen shaping the history of the Hundred Kingdoms at every turn.

Many argue this paternalistic attitude has caused more harm than good. They point at the destructive chaos of the Red Years, sparked by their premature attempts at unifying the Hundred Kingdoms, or the bloody riots that followed the summary execution of the beloved Arch-Bishop Nicholas during his Regency. Despite this, the Orders have long maintained a good relation with the common people of the Hundred Kingdoms who praise them as heroes and benefactors: the monumental sacrifice of the Order of the Sword in the Nord invasion, the selfless heroism of the Order of the Shield’s Knights Errant and the tireless public works of the Brothers Mendicant of the Order of the Sealed Temple have long since swayed the hearts and minds of the common folk.

With the collapse of the Empire, the Orders lost much of their influence, as they were heavily invested in the office of the Emperor, at the expense of both the nobility and the Church. When these two pillars aligned against them, there was little the Orders could do without resorting to war. Learning from their past mistakes, the Orders took a long view and withdrew. Though their influence might be a fraction of what it once was, their military might has not dimmed in the least, echoing the prowess of the legendary Legion that birthed them.

Imperial Remnants

With the death of Otto IV, the last Emperor, the fate of the Empire seemed sealed. The nobility used the Imperial Conclave, called by the Emperor himself, to muzzle the Orders, shackle the Church and dissolve the Legions. Without these bastions of imperial strength, nobody would have the power to challenge their claims. The Empire was doomed, never to threaten the rule of the nobles again… or so they thought. Reality was not so simple and the idea of the Empire proved much more resilient than its enemies counted on. As the situation spiraled out of control, the survival of the Empire came down to the fateful decision of the Steel Legion.

Ordered by the Imperial Conclave to disband, the Steel Legion simply refused. They pitched camp within the Klaean Fields of Argem and announced that the Empire’s capital, and all of its visitors, were under their protection. Reluctant, or unable, to challenge the Legion individually, the noble Houses delayed in their response and calmer heads were able to prevail. The problem did not lie with the Empire, they argued, rather it lay with the role of the Emperor. In the absence of an Emperor what more could the nobility want from the current status quo? The answer, of course, was the Imperial Estate.

Every noble coveted the wealth and influence that came from the title of Emperor but, even more than coveting it, they feared it would fall into the hands of their opponents. Thus, in a uniquely inspired compromise, the seasoned political minds of the nobility that attended the Imperial Conclave struck upon an agreement that pleased no one but satisfied them all: the Imperial Estate would be managed by the Imperial Chamberlain until a new Emperor could be elected, whose integrity, and neutrality, would be guaranteed by the Steel Legion and the Imperial Conclave.

To this day, the Imperial Remnants continue to thrive, funded by the immense wealth of the Imperial Estate. The Chamberlain retains control over the Mint and its Gilded Legion, as well as the Collegia and the Imperial Courts. Even if the Imperial Conclave has stripped their ability to rule on high crimes among nobles, the Imperial Courts continue ruling on low cases, granting commoners a chance at a fair hearing, assuming they can petition their case.

The Chamberlain also retains the services of the Imperial Ranger Corps, to ensure the sanctity of the far-flung properties of the Emperor. Often lending their services out to loyal imperialist houses as they are needed, they also serve as the Chamberlain’s eyes and ears to lands beyond his direct influence. In addition he has chartered the dreaded Steel Legion to defend the material interests of the Estate in view of noble aggression. This has made the Office of the Chamberlain the single biggest employer of the Steel Legion, even if they continue to supplement their income by taking on outside contracts, so long as those promote the interests of the Empire.

Lastly, it is the Chamberlain’s duty to host and preside over the Imperial Conclave every four years, a gathering of the nobility and leaders of the Hundred Kingdoms, to discuss matters of State ranging from trade and border disputes to the election of a new Emperor. Although the Empire has endured over a hundred years without a candidate coming close to election, this is still a momentous event that sees the potentates from throughout the Kingdoms gather for a fortnight of debauchery, power politics and intrigue.

The Office of the Chamberlain quickly evolved from a proscribed managerial position to a powerful force in the daily reality of the Hundred Kingdoms. By exploiting smaller titles and estates once held by the Emperors to secure votes, it exerts significant influence on the Imperial Conclave, where its neutral position acts not only to protect the Imperial Institutions and Estate, but also as a foil against the more extreme elements which seek to undermine the Imperial legacy. When even these subtle methods prove inadequate, it can call upon the military might of the two greatest fighting forces in the Hundred Kingdoms, the two remaining Imperial Legions, as well as the Imperial Ranger Corps and the ingenuity of the Imperial War Colleges.

Faith

The issue of faith in the Hundred Kingdoms is intrinsically linked to the Fall. The eldest of the two faiths, commonly called the Theist Church, does not deny the Fall itself. Rather, it denies its significance. They argue that it was mankind itself that Fell, not the Divinity. The divinity was cast out from heaven for its failure to guide humanity on the path of righteousness. In their doctrine, the Fall is the literal and figurative punishment of man by God, the Theos. For our failures, He cast away mankind’s greatest champion and has left us to languish without His guidance. The few believers that were spared from the Fall were Gods Chosen, and following them

is the last chance mankind has at redeeming itself. It is thus Humanity’s duty to rectify this grievous state of affairs, to move away from its life of sin and decadence and follow the Chosen of the Theos back into the light. The Theist Church is one of high ritual and deep tradition, stretching all the way back to the original practices of the Old Dominion, before the pride of man corrupted it. They enjoy tremendous support from the nobility as their doctrine of the ‘Chosen’ has been graciously extended to the nobility through the divine right of kings.

The Deist Creed, on the other hand, argues that the Fall of the Divinity was due to Mankind and its flawed vision of Perfection. They argue that God is a perfect distillation of Man, rather than Man an imperfect copy of God, and that our limited perception of this Perfection twisted what was once whole and pure through need and prayer, warping it so badly it Fell. They argue that the only way for humanity to worship the divine is by choosing to worship those Aspects we each understand and embody the best. Thus, to come closer to divinity one needs not be born among the ’Chosen’, but to embody those Aspects of the Divine as closely as possible.

Unlike the Theist Church, the Deist Creed is not a centralized religion, rather a religious movement, so forming a consensus on what exactly the Aspects are is a matter of heated theological debate. Their dogma of enlightenment and advancement through self-improvement and hard work rather than abasement and obedience, has spread like wildfire among the downtrodden, who see in this philosophy a chance to rise beyond their limited means.

As a result, religious disputes have become an extension of social differences making confrontation all but inevitable. The power of the Faith was kept in check by the Emperor and the Orders but, with the collapse of the Empire, both churches have seen their influence grow in leaps and bounds. While still limited to fielding only their dreaded bodyguards, the fanatic Sicarii, by ancient Imperial decree, the time is soon coming when neither Order influence on the Imperial Conclave nor feudal resentment at armed forces other than their own will keep the churches from resolving their theological disputes on the field of battle.