City States

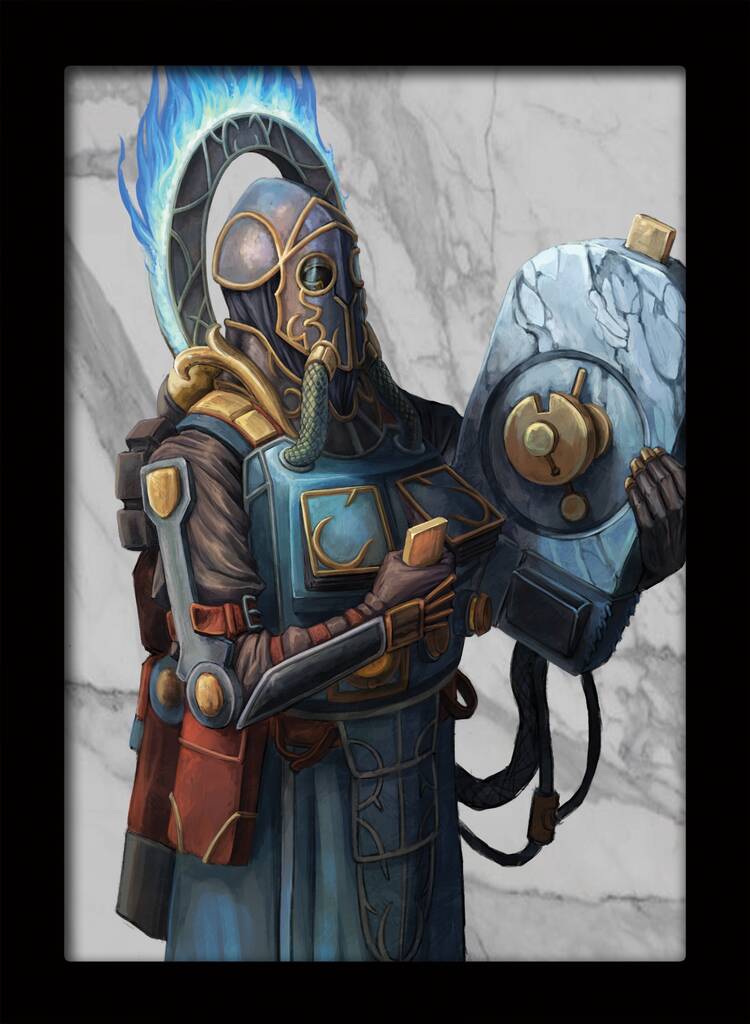

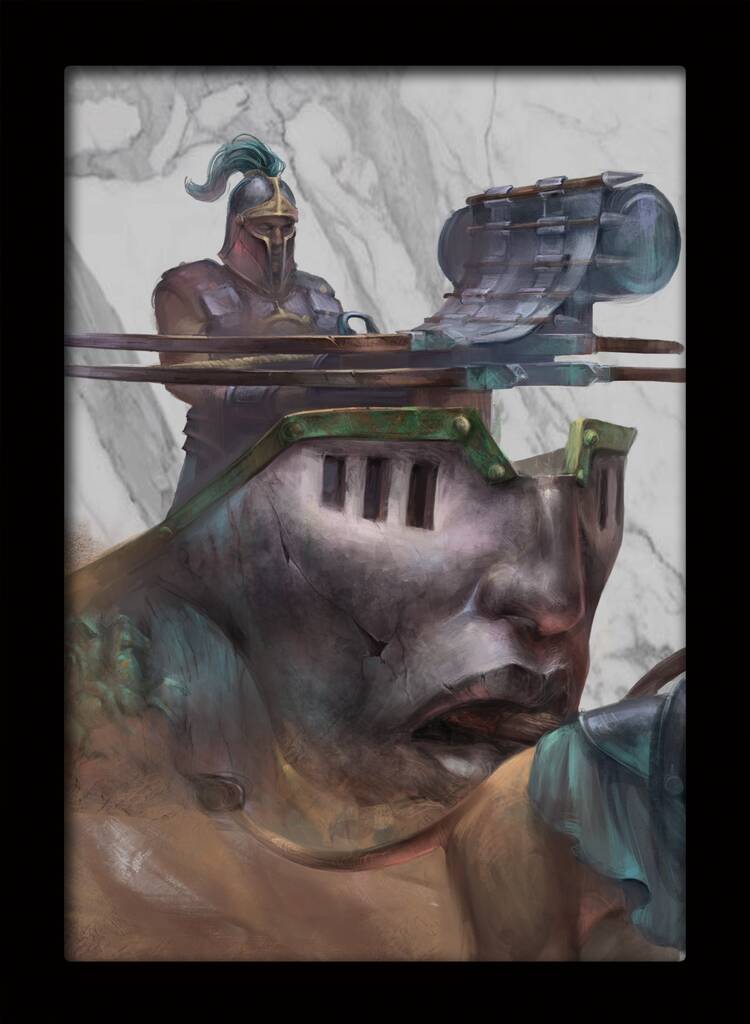

Safely smuggling and zealously guarding the amassed knowledge of the Dominion, no civilizations can match the City States’ ingenuity, their technological brilliance or the discipline of their phalanxes.

“…a beacon of light, a fountain of knowledge, science and progress, they hoarded

wisdom in massive libraries, before we relearned how to print.”

– Tosquil de Gaalen Dopan, Trobadure

While the Hundred Kingdoms were being born in a wave of desperate refugees, violence, and hunger, the City States were flourishing, picking through the greatest secrets of the old Dominion and delving into the perplexities of archemy and divinity. Today, they are the greatest repositories of knowledge and the inheritors of the glory that was once the Old Dominion of Man.

While the Hundred Kingdoms were being born in a wave of desperate refugees, violence, and hunger, the City States were flourishing, picking through the greatest secrets of the old Dominion and delving into the perplexities of archemy and divinity. Today, they are the greatest repositories of knowledge and the inheritors of the glory that was once the Old Dominion of Man.

At least that is what the Locutors of the City States would have one believe. It is true that while the Hundred Kingdoms were born from the desperate rush of thousands of refugees, the City States had already been founded on the highest principles of philosophy, ethics, and education available to mankind. In fact, the entire existence of the City States is owed to the presence of their founder, Constantius Domulexor.

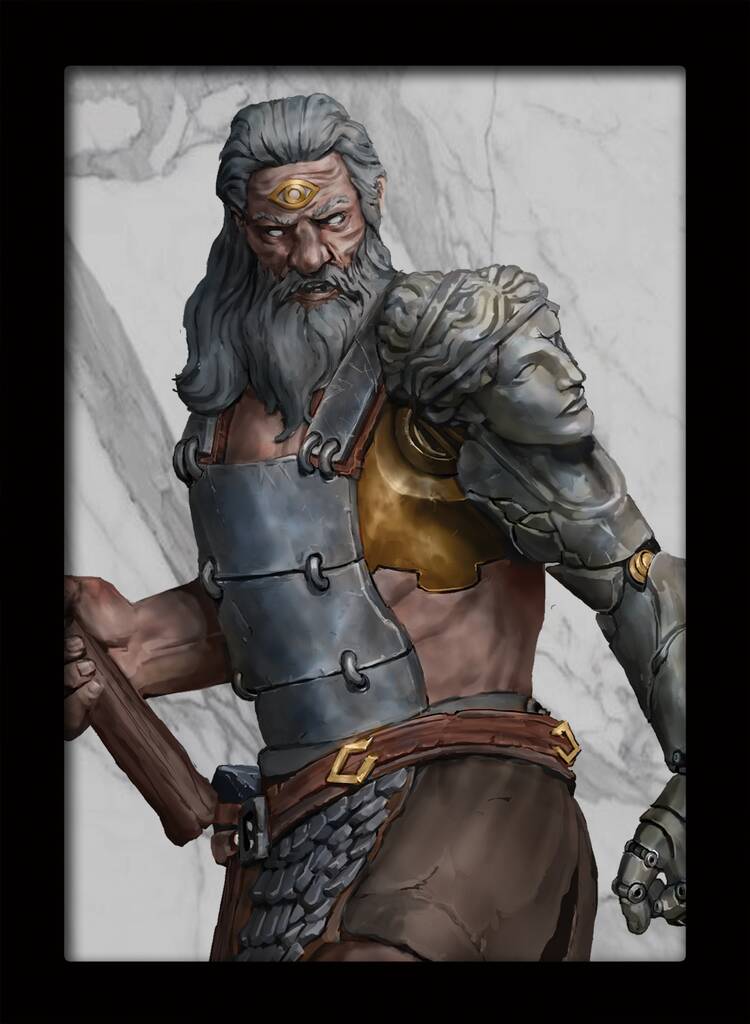

Born Platon of Chorae, he started as a humble butcher’s apprentice, only to rise to the pinnacle of secular power within the Old Dominion, becoming the Maistros of the Dominion’s Collegia under the academic name of Constantius Domulexor. It was Constantius and his colleague, the unnamed First Magos of the Collegia, who identified Hazlia’s creeping madness. They, two of the most powerful and influential individuals within the Dominion, delved deep into the secrets of the divine and the Primordial, plumbing mysteries on the nature of divinity and power that have thankfully been lost. Both individuals were deeply changed by their research, and, while the First Magos sought to use his knowledge and power to kill his God, Constantius resolved instead to safeguard and protect mankind from the coming cataclysm as best he could. Using once more the forgotten name of his humble origins to ensure secrecy in the first stages of his schemes, Platon took on a subtle task of momentous proportions: the transfer of an empire’s amassed knowledge.

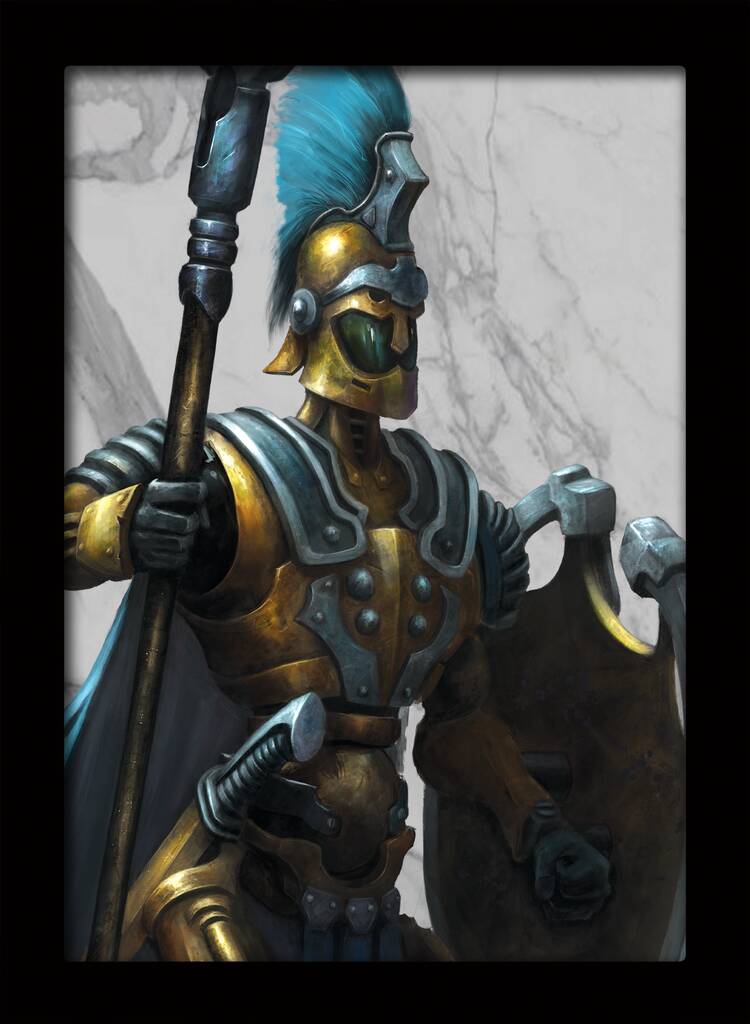

Thus, the foundations of the City States were laid. Craftsmen, scholars, and workers were secretly encouraged to emigrate even as the libraries of the Old Dominion were copied and sent with them. As the collapse of the old Dominion accelerated, even the thinnest pretenses of secrecy were abandoned. Entire libraries were ransacked, and countless legion reinforcements were diverted to serve as guardians for the burgeoning cities. Even some of the Bred were saved from the great purges that followed, becoming productive members of the growing City States.

Platon’s knowledge of the workings of divinity allowed him to send a Primordial seed to each of his cities, which would, with worship and belief, grow to become patron Gods to each city, protecting them from Hazlia’s baleful influence and unknowingly laying the foundations for the single greatest technological advance of man: the science of archemy.

To ensure the success of his vision, he dared what no mortal before him had attempted and stole a small but critical portion of Hazlia’s mantle to keep the fallen god from turning it on mankind. Worried that he might eventually succumb to the same fate as his God, Platon sought to divide and contain this gift, placing himself at the heart of every City that was founded in his vision.

So, with a healthy population, a dedicated corps of Guardians, a benevolent patron god, the accumulated knowledge of mankind, and himself as an incorruptible philosopher king guiding them, it was Platon’s dream that each of these cities would become a utopia from which man could reclaim the planet. But so worried had Platon become of the Divine pitfalls and the corruptive nature of the power he knew he would wield that he fell for an even more timeless foe: hubris.

While the scientific principles behind his efforts may have been sound, his time was running out, so his process was rushed and his vessels flawed. The transference was incomplete, and the cities were left to their own devices, ruled by pale shadows of what Platon had hoped would be divine philosopher kings advised by an incorruptible council. Impaired by their own deficiencies and scarred by the terror he felt in his final moments as his science and technology turned against him, the governing councils of each City ruled as best they could, but to no avail.

Within decades, little unity remained amongst the City States. Fed by the burgeoning paranoia of the Councils, all efforts were bent to securing the future and prosperity of the City States against a divine foe that had already been defeated rather than focusing on safeguarding mankind as a whole. Resources were hoarded, and relations between the cities soured quickly.

Fearful of upsetting the status quo, the Councils proscribed almost all growth and development but what they could control, and, almost overnight, archemy and clockwork became the driving force of industry within the City States. With no overarching will to guide them, they soon became independent City States, each warring with the other to maintain what dominance and resources they could secure.

After decades of repression and warfare, it should come as little surprise that almost half the City States rebelled against their own councils, particularly among those cities where the damage from the failed transference was the greatest. Some of these rebellious cities imploded spectacularly, their citizens fleeing north to the Hundred Kingdoms or finding refuge in other, more successful, City States. Those City States that endured fall within two broad categories: those that fell under the sway of demagogues and the plague of democracy and those that fell under the iron-fisted control of their patron gods unleashed.

Today, that is how the City States stand: split among the Demagogue, Militarist, and Academic Councils, squandering their glorious heritage and advanced technology while challenging each other and any who might threaten them for supremacy.

Mind, Faith and Politics

Designed to be perfect societies, each City State was meant to be ruled by its greatest minds, fueled and united by its patron god, and with all of its people inspired and active citizens.

The execution of the design was flawed.

Scholae

Scholae Populist States

Populist States Religious States

Religious StatesThe Scholae

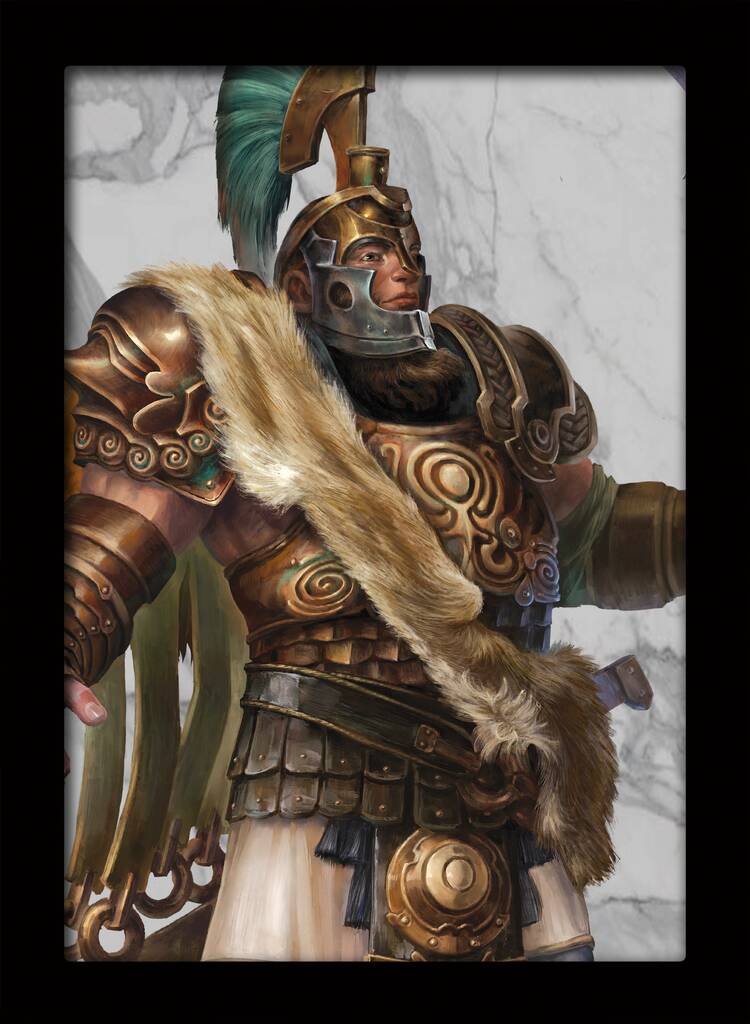

One has but to catch a glimpse of Pallas, crown jewel of the City States, to understand the awesome power that the Scholae wield. Its towering white walls gird the city like the arms of a lover as the gold cupolas of its trading houses shine day and night under the glow of the flaring phlogiston stacks that rise through the city like the dreams of a maddened genius. Crowning this vision and rising from the center of the city in a vision of white and gold, lit by the lurid lights of its own accomplishment, is the Acropolis upon which rests the Lyceum, seat of all power in the City State and beyond.

Pallas is the city around which all City States have been modeled, a shining beacon to the potential of mankind and the vision of its founder, Platon. Unfortunately, despite his best efforts, Pallas remains a rare jewel amongst the City States, true to the vision and principles to which it was founded while other cities have strayed. Some, like Helias or Rhodea have merely lost focus, but others like Acheron or Leutria have completely abandoned the Scholae and their gifts and embraced the power of the gods and masses, respectively. And at the heart of this Schism lies the mad ambition of their founder and his hubris.

When Constantius Domulexor envisioned his dream of a mankind free of the yoke of worship, he knew well that one could not forge this dream overnight, nor perfectly. No matter his efforts, time and human nature itself would conspire to rob mankind of its own future.

Now it must be understood that, aside from the Anathematic, no other human had grasped the secrets and nature of primordial power than Constantius Domulexor. It was in fact he who coined the three principles of power that have formed the bedrock of modern primordial studies: that power corrupts, that belief is power, and that power calls power. Hurling himself into his project and studies, Domulexor worked like a man possessed. The more he understood of the twisted mind of his God and grasped the full breadth of his plans, the more horrified he became by what he witnessed. Domulexor saw that his original plan lacked the depth of conviction and scope necessary to survive Hazlia’s attention should the Anathematic fail at his deicide. His plans had to be changed, and changed radically, to ensure no menace like that ever rose again.

His efforts, the true depth and breadth of which are hidden from almost all mortal eyes but those of his Scholiasts, lacked the decades of planning and breadth of resources he had once enjoyed. With the majority of his wealth and influence tied up in the foundations of the city states and the incipient collapse of the Old Dominion, Domulexor was forced to undertake his most daring and dangerous project.

Delving deep into the secrets of divine power and its primordial origins, he sought to become a god who could not be corrupted by power, whether his own or his followers’. This would require that he became a weak divinity, though one that remained powerful enough to usurp his patronage of craftsmen and scholars from Hazlia – a task that he calculated would be easier now, given that Hazlia had long since abandoned those aspects to focus on his role as Lightbringer and Pantokrator.

Pressed for time, he struck upon a desperate plan. Taking on the persona of Platon, he stepped forth from his role as Maistros of the Collegia and became the patron of the City States. Venerated, but not outright worshiped in this role, he would gain the trickle of power he needed to start his plans. What unspeakable experiments, moral concessions and mental trauma he underwent can only be speculated, for all knowledge of what he did in order to succeed at his task was wiped clean.

But succeed he did. The only cost being his humanity and sanity.

Not only did he usurp the portfolio he needed from Hazlia, but further sundered his consciousness into a host of vessels, coldly reasoning that as a council he would be harder to corrupt and be afforded a better chance of spotting his own corruption. Thus was the Scholae born.

For years, even decades, this plan worked. The Scholae used the knowledge Platon had discovered and their newfound divine mantle to guide the City States into a golden age of discovery and prosperity. The City States thrived under the controlled supervision of the patron gods they installed. Their mere presence siphoning away the corrupting power of worship from him and safely drained to create Phlogiston, the incredible energy source he used to power the awesome machinery that the City States had developed under his guidance. In time the Scholae replicated itself, a copy of it having been installed in the Lyceum of every City State.

In time though, the price paid for his divinity and haste with which he moved came back to haunt him. His traumatized mind should never have been invested into new vessels, especially ones chosen for their availability rather than their compatibility. Madness slowly seeped into the councils, and with it, chaos. Contradicting orders, abandoned projects and the inhuman expectations of his followers mounted on each other. This process was particularly pronounced in those city states that had received a second generation Scholae, as the recompilation made the errors more pronounced.

Madness and paranoia crept into the halls of the Lyceum, with facets of the Scholae suspecting each other of corruption and turning on each other. With each death, the Scholae fragmented further, losing critical knowledge and information required to continue running the city. It took only a few short decades for chaos to overwhelm most of the City States.

In some, namely Leutria, Eubron and Laurion, the mobs broke into the Lyceum and, horrified by what they encountered, purged the Acropolis, and established fledgling democracies that sought to fully integrate every member of the cities’ society into governance. These cities even opened their doors to the few Bred refugees and slaves that had managed to escape the fall of the Old Dominion, granting them equal rights and a voice in the governance of the city, in principle at least.

In others, the rising frustrations of the populace turned to prayer and the weakened Scholae were unable to contain the nascent power of the patron gods. In Acheron, Tauria and Lycaon, the patron gods, awakened from their slumber to witness the truth of their own incarceration and exploitation, these nascent gods stopped only to slaughter their captors before taking command of their Cities. These cities thrive under the power and watchful gaze of their gods. With every facet of life closely aligned with the gods’ visions, their grace and blessings flow freely, but dissent is ruthlessly suppressed.

Only Helias, Rhodea and Pallas managed to avoid this fate. Here the Scholae managed to fend off the incipient madness, quarantining and sectioning off those segments of themselves that had become corrupted, staving off the growing madness. In Rhodea this manifests in the grandiose megalomania of the cities’ projects and workshops while Helias’ fixation on development and wealth have driven it to heartless extremes. Today only Pallas stands as a beacon to the vision of what the City States were meant to be.

The Populist States

While the history of the Transcendent States dominates bardic epics and the imagery of Pallas has inspired an entire School of Art in Galania, it is the political system of the Populist Cities that has served as inspiration for endless conversations. From radical groups in shady inns to philosophical youths of the nobility in the comfort of their soirees, the idea of a society where the individual is valued enough to contribute to a State’s policies has intrigued thinkers far beyond the borders of the City States.

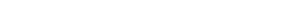

Most look at this unprecedented concept at face value; these societies have embraced all within their walls, presenting a seemingly seamless coexistence which promotes discussion, cooperation and constant societal evolution. And indeed, visitors would be quick to notice the citizens of such a State walking freely and equal in its streets. They would see them gathering in the Agora, where the Ekklisia of citizens would discuss and decide on the fate of its own city, from simple matters like the restoration of streets or the erection of new statues to enhance the city’s splendor, to big works like the expansion of the walls or the declaration of war. Human and Bred, be they Satyrs, Fauns, Minotaurs or Centaurs, make up their state’s mind, even as they listen to its voice; a collective society but one which also never loses sight of each and every person in its ranks. It is a perfect union of individuals embodied by its marble statue with a firm fist made of different fingers; one which rushes with passion and force to meet its destiny and crash its enemies.

But should one look closer at this perfect image, one would notice the cracks in this marble statue’s face; for States with a unified voice, the Demagogue Cities are in their core more divided than most. It would be a philosophical debate in itself to pinpoint the source of this division; its agents are apparent. Deprived of the contingencies Platon’s overseeing philosopher-kings would offer, the procedures of the Ekklisiae would soon inspire aggressively ambitious individuals and opportunists with a talent for persuasion. In time, the claim to electoral offices would become a profession in itself, one whose success depended on an inspired and loyal following that would readily support one’s views. In a society with obvious divisions in creeds and races, the avenue to success was not hard to detect.

During those philosophical discussions in lands far beyond, there is always one who rushes to remind the rest of the sad truth: much like the rest of Platon’s experiment, these City States have failed, subject to the predations of demagogues that seek to capitalize on their systemic flaws. One could indeed see free citizens shout their prices with gusto from behind stands and shops with anything from silk and spices to fresh fish and vegetables that they have gathered by hand. They would perhaps also notice how a human would scarcely look at the Bred seller and vice versa, or how one would openly scorn those who support opponents in the Ekklisia.

The scars on the society of Demagogue Cities extend far beyond the obvious and the ferocity of division is perhaps even harsher between the Bred and the humans themselves. Calling a Satyr a “Faun” even by accident could very well result in one’s body to be found among the morning’s catch. Doing the opposite could spawn a grudge that would never be forgotten and would potentially be repaid with great imagination and far beyond the limitations of mere insult, no matter how grave. The degrading names that humans use for different types of Bred (calling a Minotaur a cow is a favorite, even if rarely in one’s presence) have not only been adopted as insults by the Bred but embraced with gusto. While perhaps less obvious, the divisions among humans are no less vicious. When listened to with care, those inspiring discussions in the Agora are rarely much more than venomous rumors and veiled, or not-so-veiled insults that rarely have anything to do with the matter to be decided. The ideal of logic and the prevailing structured argument has long been abandoned and the Ekklisiae have become glorified slandering platforms. Trade wars have been declared on purely political grounds, that have financially crippled entire families.

When such tactics prove to be insufficient, violent clashes, coups and tyrants are ready to appear when offered enough support, only to be overthrown, sooner rather than later. This process has been repeated so many times and with such consistency that Vomophonos, in his comedy “Theemos”, would have its protagonist be asked “Τύραννον εἶχες;” (“Did you have a tyrant?”) when he claims he comes from a populist state, as if this would verify his claim. Apart from dry humor, however, there were much more lasting repercussions.

Coups and tyrants would often find support among the oppressed Bred, who would in turn see their rights suffering further when populism would be restored. What’s more, the law often foresees that one’s family will be held accountable for one’s transgressions, having failed to produce a worthy, lawful citizen. Voting rights will be revoked for a generation or more, either completely or for some types of votes, until eventually, some citizens will be ever so slightly less equal than the rest. Most Bred and some human families today are allowed to vote only on specific matters of lesser importance, while only few could run for office, even if they thought they did stand a chance to win. More often than not, these join the military, whose regular rank-and-file soldiers lack many voting rights anyway but have a guaranteed salary and place in society. In the end, that too serves the demagogues that saw them in that position at the first place; the might of the City is a favorite subject of the Ekklisia.

The damage to Platon’s idea of a unified society was not done overnight and in many ways that is where its “success” lies. Little by little, the differences, not only those physically apparent, but also in views, opinions and ideas would be marked with lines that would only deepen with each generation. Yet somehow, despite these adversities, or perhaps because of them, these Cities have no less strength and majesty to present. Even if constructed to satisfy a successful demagogue’s ego, impressive walls and giant statues have been erected, while entire fleets have been forged and Bred-enhanced armies have been kept in excellent condition to inspire one’s fearful supporters. What if those walls are named after them, if the statues depict the megalomania of some or if the names of the fleet’s ships carry the names of individuals that did more harm than good? The strength and might they both project are real, and the forces that can be fielded can wreak havoc. And the moment a demagogue seeks to create enemies beyond the city’s walls, this strength will prove just how real they are.

The Religious States

It is a testament to the scope and depth of Platon’s design that, in many ways, the easiest part of his plan was the forging of gods out of the primordial shards he had secured for each City. The people of the Old Dominion, after all, had been shaped by a theocracy, their everyday life dominated by a religious culture, forged by a mosaic of multiple tribes and peoples, as well as an expansive pantheon. Stripped from its idealistic endgame of a perfect society, Platon’s enterprise was a true scientific miracle that saw gods created by the design of a mortal, an unparalleled success of human ingenuity.

The shackles that contained these new gods, each further restricted in the confines of worship and influence of their respective City States, were indeed placed ingeniously. But the strength and endurance of their manacles relied on the creation of an ideal society where great philosopher kings ruled in harmony and wisdom. With that part of the plan in shambles, the chains of these deities would weaken, and cracks would prevail upon their gilded prisons; their limitations would suffer and the thirst for absolute freedom would slowly consume them. In most cases, this would fuel an unending power struggle between them and the City’s Scholae, academics and demagogues. But in some Cities the patron deities would expand their influence and purpose far beyond those of their intended roles.

In Milios – by far the strongest naval power of the City States and a dominant force even beyond the pelaga of the Cities – while the goddess Athrastia does not dominate the everyday life and politics of her city, many see her influence behind the city’s admirals, who worship her as a fickle and vengeful mistress that mirrors their seas. But it is perhaps no coincidence that those deities that have far expanded on their intended roles were originally designed as a triumvirate of military command, there to ensure the safety of the City States. Whether because of the abundance of worshippers that their military societies offered, their very nature or chance, three gods above all else would come to dominate their Cities’ life and cultures.

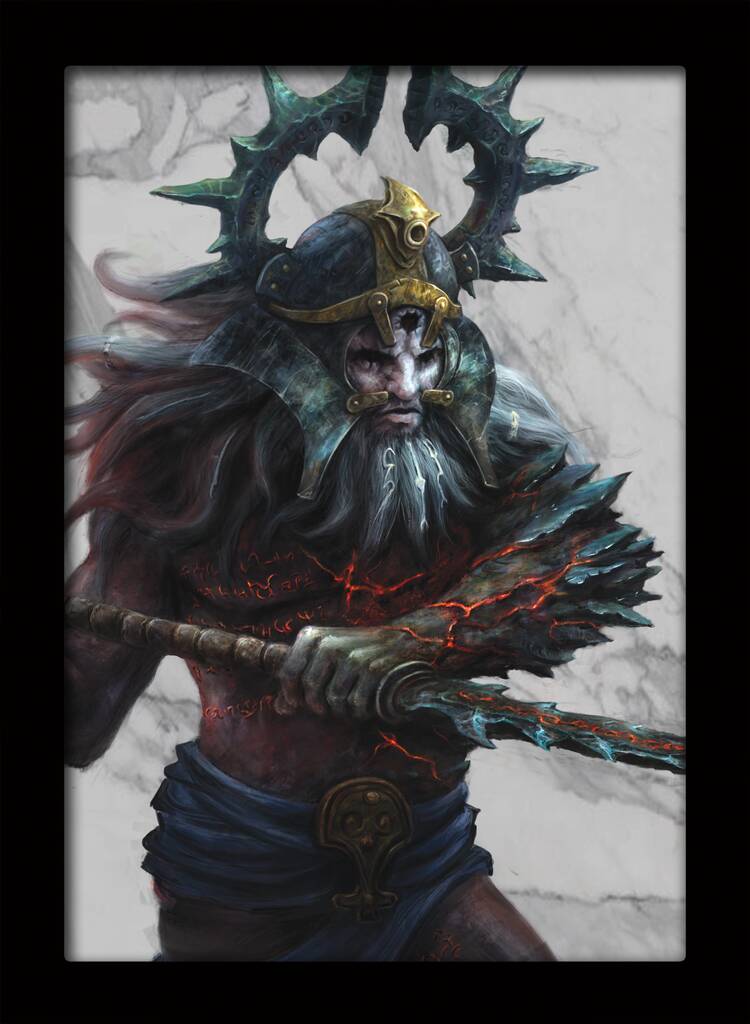

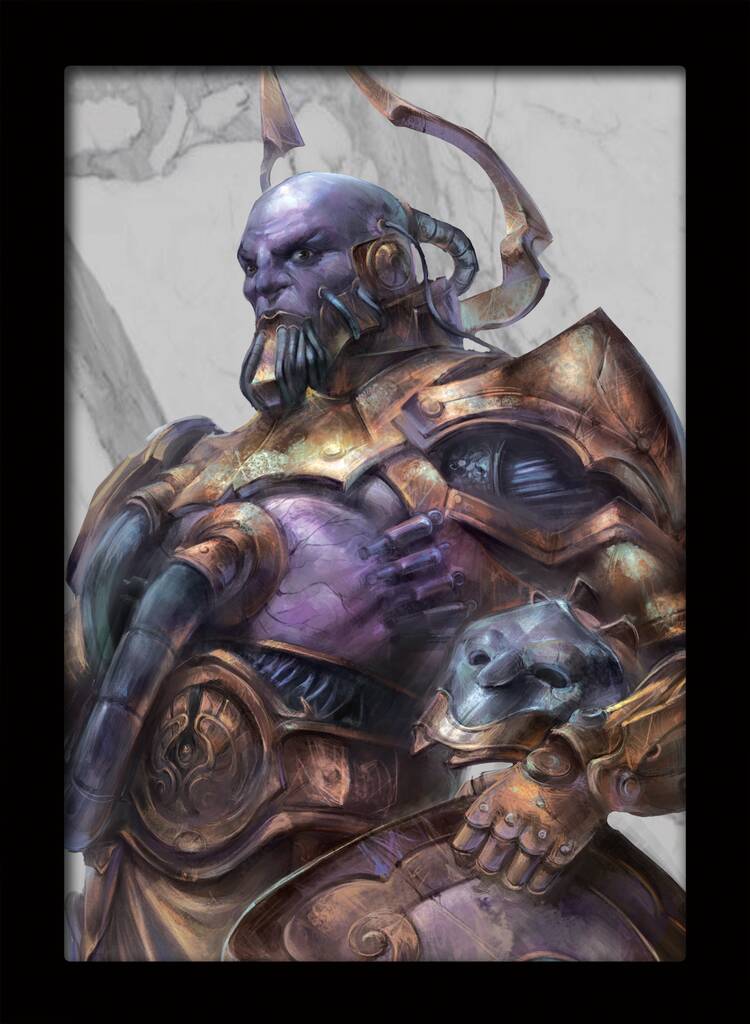

In Tauria, Minos would be venerated with gusto, his double-edged axe adorning the shields of his warriors and his horns dominating his colorful city’s landscape. Celebrated by his people for his disposition, ever willing to break his own rules, but also feared for his stern judgment and even vengeful wrath, Minos is perhaps viewed as a Warrior King, one who makes allowances readily but whose mood-swings can be unpredictable once an unseen line is crossed. His critics often dismiss him as reckless, petty, and self-indulgent but an observant scholar would perhaps hesitate before adopting such views. Minos’ warriors are some of the best in the City States. For all the feasts and colorful celebrations, Tauria remains a heavily militarized and structured society. His warriors have defended their patron’s influence and lands from other City States, often through displays of power that one could portrait as unnecessary, petty or vengeful. Yet, the Warrior Bull has rarely turned his aggressive attention towards the City States unless provoked, some claim unwilling to risk disrupting the balances that still ensure the partial success of Platon’s plan. Tauria’s forces have instead ever looked to expand towards the Allerian Plains. Multiple campaigns and wars against the Telian Empire, or the Hundred Kingdoms later, have been waged, that, through both victory and defeat, have inspired timeless epics of legendary warriors, massive battles and heroic deaths.

Minos’ stricter and more ruthless counterpart reigns in Lycaon, where Aecos would ensure the city’s name would become a synonym for strength, cunning and ruthlessness. His efforts to break free of his shackles are as relentless and single-minded as they are calculative and patient. It is perhaps a blessing that Aecos’s limitations remain seemingly stronger than Minos’s but the deity is nothing if not a cunning commander. It is no coincidence that no city and few towns or settlements exist near his, and the entire Lycopaethion, the Valley of the Wolf, is riddled with ghost towns and abandoned ruins of temples to other deities. If directly challenged through force, the challenge is answered with spear and sword, quickly and efficiently, and it is said that even the Nords have learned tales of ruthless warriors with Lycaon’s initial on their shields. Still, Aecos understands that it is preferable to convert than to kill would-be followers and that the way to freedom is not a battle but a campaign. Where circumstances allowed, rather than eradicating a settlement, crops have been destroyed, land salted and animals stolen or killed, the missions often used as training for child cadets. In time, the would-be settlers would either leave or try their luck in the existing towns or the city. If they did not come to worship him, then their children or their children’s children would. Ever few of words and despising fanfare, Aecos would see Lycaon become a symbol of military strength that the entire world would come to know.

Last of the intended triumvirate was Radamanthos, patron of Acheron. Unlike his counterparts, Radamanthos was intended as a thinker and a strategist, not a mighty warrior or commander. Baptized as he was with one of the many names that once belonged to the Seer, the deity was soon venerated as a judge of the dead, and the god readily adopted the mantle, with eyes sternly turned to the rising threat in the East. It is perhaps for this reason that he approached both Minos and Lycaon, trying to ensure that all three fulfilled their intended roles as a triumvirate. And it is perhaps for the same reason that the two rejected his offer.

Afraid of the possibility of his own corruption without his counterparts and terribly aware of his duty as the first defense against Hazlia’s influence, Radamanthos turned to his worshippers. Choosing two, he attempted to replicate Platon’s experiment and to elevate two mortals by his side; Triptolemos in the place of Minos and Demophon in the place of Aecos. It is unknown precisely to what extent his endeavor was successful, or how effective his effort to counter his corruption has been. Under the three deities, however, Acheron has successfully endured and even prospered in the shadow and under the constant threat of the Old Dominion and the Tribes of the W’adrhûn. And yet whispers and shadows in the city seem alive of late. At the feet of Radamanthos’s giant statue that stares ever to the east, where Triptolemos and Demophon reside, a new inscription has appeared: “Θνητός γεγονώς άνθρωπε, μη φρόνει μέγα”: you were born mortal, Human, do not think too highly of yourself. While some see this as a wise caution from their gods, to remain humble and respectful, reminding them of the dangers of hubris, others fear both its origin and its true meaning.

With a careful selection by Platon, of names, iconography and symbolism, all familiar from the endless, vague and intricate scriptures of the Dominion, the transference of belief came to his designed deities almost naturally. Acheron’s seasons today are riddled with Mysteries, sacred days, rituals and celebrations to strengthen the triumvirate. Lesser or greater aspects that Hazlia had assimilated from his own Pantheon were once more redirected into these shards, depriving the Pantokrator of small but vital portions of the power and dominion he was possessing at the peak of his power. Shackled by the contingencies built in the process and method of their very creation, these new gods would wound Hazlia’s all-powerful eminence, while avoiding the dangers of corruption. But with those shackles gone, one can’t but wonder where the unintended expansion of these deities will lead.